Inside China's Real Advantage: Manufacturing at Scale

Notes from Liyang, China's battery capital, and the infrastructure reshaping global supply chains

The following reflects my personal perspective. For another investor's widely shared takeaways from the trip, see here.

Observers often fixate on the most visible layer of China’s tech stack: consumer-facing conveniences like mobile payments, fifteen-minute food delivery, and dockless bikes. These can make for good investments — we regularly cover them at Tech Buzz China — but they are primarily business model innovations, increasingly familiar, and replicable with modest effort. In my opinion, they do not represent China’s true advantages, the ones that resist replication.

What proves far harder to replicate, and far more consequential, is the invisible layer: China’s manufacturing base. This is the part of the ecosystem that actually reshapes global supply chains, yet it remains the part most visitors never see and, in many cases, never think to see.

I was excited, therefore, when a private investor approached me to curate a trip for a group of energy executives and investors with the intention of understanding how China manufactures at scale, how new energy moves through factories and supply chains, and what execution looks like on the ground.

We largely bypassed the usual hubs. Aside from meetings on humanoid robotics, a sector we already cover in our standard deep-tech trips, we spent over half of our time on production lines, visiting six manufacturing facilities spanning the energy stack: power batteries, solid-state batteries, solar modules, power cabling, transformers, and EVs.

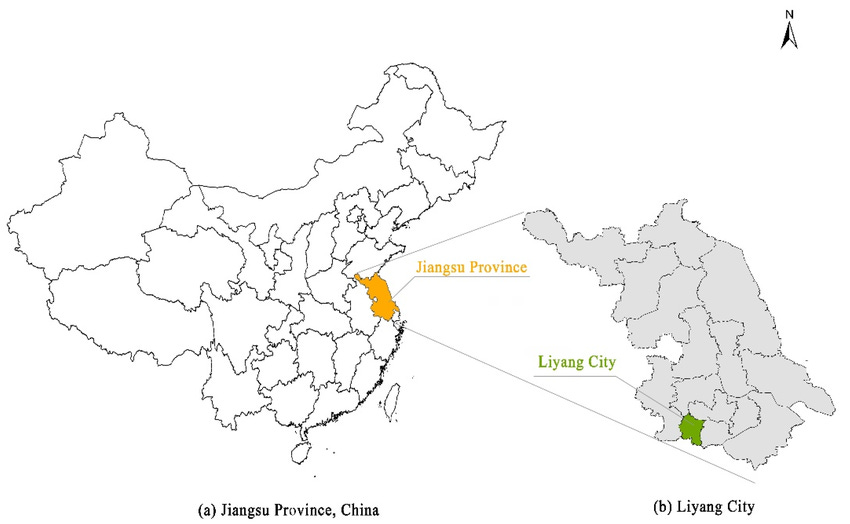

The center of gravity for the trip, and an entirely new addition, was Liyang, China’s battery capital. Located in the Yangtze River Delta, roughly an hour from Shanghai by high-speed rail, Liyang is a county-level city of about 800,000 people. Once known as the “Garden of Eastern China,” a tourist destination for wealthy urbanites, it has quietly transformed into one of the country’s most important nodes for battery manufacturing.

Liyang is a county-level city in Jiangsu province, about 80 minutes away from Shanghai by high-speed rail.

Today, Liyang hosts more than 100 power battery companies, anchored by CATL’s massive Jiangsu production base, and generates over 100 billion RMB (USD $14 billion) in output as well as ~5% of global power and storage battery production. It also leads in green steel and smart grids. Battery and physics research institutes, alongside university collaborations, support talent pipelines and applied research capacity.

We spent two full days in Liyang, which is unusual given how compressed our schedules typically are. But understanding the mechanics of China’s energy manufacturing dominance requires leaving the boardrooms of Beijing and Shenzhen. You have to go where the infrastructure is.

Below are the main things that stood out to me, organized not by the sequence of visits but by significance.

1. China’s Manufacturing Advantage Is a Deliberately Designed System

What stood out most in Liyang was not any single factory or company, but the system that made all of them possible. Chinese manufacturing in energy is not organized around individual champions operating in isolation. It is organized around place, specifically county-level cities and the industrial parks that anchor them.

Liyang illustrates this clearly. Administratively, it functions as a county-level city within a larger prefecture, a structure familiar to Indian visitors but often puzzling to Americans: a small town (though 800,000 people qualifies as such only in China) operating under a larger city’s umbrella. Strategically, Liyang chose over a decade ago to transition from a tourist and agricultural town to an industrial center. For Liyang, that meant an early bet on power batteries and securing CATL’s expansion plant.

This strategy materializes through industrial parks housing nearly all the factories we visited. These are not mere clusters of manufacturing facilities but deliberately engineered environments integrating land use, utilities, logistics, housing, and deep connections to research institutions and vocational training. Local governments don’t zone land and wait. They design environments around specific industry needs, coordinating closely with anchor firms, suppliers, and research partners.

Competition drives the system’s effectiveness, though not in conventional terms. Liyang isn’t alone in pursuing batteries or new energy; multiple counties, often within the same province, share similar priorities. This shifts competition from policy signaling to execution quality: how quickly can they prepare land, connect utilities, issue permits, and support production ramp-up? How effectively can the local municipality recruit trained workers, house them, and retain them? What about research personnel? Subsidies matter but rarely prove decisive. Companies prioritize operational readiness and sustained support.

This execution emphasis manifests in process design. To give an example, Liyang is pushing its newest business-friendly program, called “1220”: shorthand for one working day to complete business registration, two working days to complete real estate transactions, twenty working days to issue construction permits. Sometimes companies begin building under conditional approvals while final paperwork processes. This isn’t privilege reserved for national champions; it’s how the system functions.

Supply chain density reinforces this advantage. Industrial parks explicitly attract and relocate entire supply chains, not just individual firms. The agreement with CATL wasn’t merely that they would establish a plant there but that Liyang would help all their suppliers relocate as well. This concentration allows many companies to source most inputs within a few hundred kilometers, which lowers costs, shortens iteration cycles, and simplifies cross-stage coordination. Once established, such systems become extraordinarily difficult to replicate, even where labor or land appears cheaper.

CATL’s Liyang plant was designated a Lighthouse factory by the World Economic Forum in 2023.

2. Within the System, Speed Becomes a Compounding Advantage

Once the system comes into view, speed becomes impossible to ignore, not as cultural trope but as deliberate engineering continuously reinforced from local governments to factory floors.

The compounding begins with infrastructure. One steel-intensive manufacturer we visited sources so heavily from a single global supplier that the supplier purchased and operates a dedicated ship for their deliveries. The manufacturer built its own port to ship thousand-ton finished products directly to Shanghai, an advantage unavailable elsewhere in China, much less globally, and sufficient reason to stay despite tariffs.

Every company we met moved beyond conventional vertical integration to build their own manufacturing equipment, not comprehensively but surgically. They identified steps where off-the-shelf machinery proved too slow, costly, or poorly tailored, then designed custom solutions.

These layers compound. More than once, speed alone determined who won a project. Global competitors matched or exceeded quality but delivered on the order of years. Chinese suppliers delivered in months. Scaling itself becomes a learning process: as companies scaled, they accumulated experience and accelerated further. Speed becomes self-reinforcing because every system layer rewards it.

From outside, this intensity looks exhausting. From inside, it’s rational. Time is the scarce resource. Capital, labor, even technology can be substituted. Lost time cannot. China’s manufacturing advantage isn’t simply moving fast. It’s that speed itself has become a compounding asset.

3. Profitability Is Rarely The Core Objective

After seeing how the system is built and how speed compounds within it, it becomes clear that profitability occupies a different place in the hierarchy of goals. This is exceptionally confusing to investors, and with good reason.

In many Chinese sectors, high profitability signals success but also vulnerability. Excess margin attracts competition, particularly in environments where supply chains are shared, capabilities diffuse quickly, capital expenditures take time to recuperate, and business cycles can be brutal. The solar sector offers a bloody example. Operating with lean margins can function as a defensive posture, reducing the incentive for others to enter aggressively.

This helps explain why scale is often prioritized over near-term financial optimization. Scale brings bargaining power, learning effects, and endurance. It increases the cost of displacement. In a system where competitors are numerous and persistent, the ability to endure matters more than the ability to extract short-term profit. Profitability still matters, but it is treated as a constraint to be managed rather than a metric to be maximized.

The concept of involution — roughly, competitive intensity that becomes self-destructive — captures something real but incomplete about Chinese manufacturing. Foreign visitors ask when margins will improve, assuming profitability is the primary goal. In the environment we saw, it isn’t. Endurance comes first. Margin expansion is earned later, once scale and position are secure and paired with groundbreaking innovation at irrefutable scale. CATL has achieved this combination. Huawei has as well. But these are rare winners.

China’s manufacturing system is optimized for survival under pressure, not comfort. That pressure shapes how companies think about success, risk, and reward.

One trip attendee captured this tension concisely in his viral takeaway:

“I don’t know if Chinese manufacturers will ever make money but I came away not wanting to invest in any manufacturing business in the rest of the world.”

The concern is legitimate. But it’s worth considering whether this perception is precisely what the sector intends to project. Manufacturing here is not a business where you sit back and collect profits. It is a relentless grind unless you are among the very top players, and the warning embedded in that reality may serve as its own barrier to entry.

4. The Energy Transition as Organizing Belief

After spending time inside China’s energy manufacturing ecosystem, the pressure we observed only makes sense if you zoom out. Speed, thin margins, and relentless cost discipline require a deeper organizing belief. In this case: the energy transition.

China’s push toward zero emissions has mobilized broad alignment across multiple motivations. Part is strategic: energy independence and supply security matter. Part is deeply practical. Air quality remains a lived issue. On this trip, Shanghai’s air quality index hovered at levels unacceptable in many countries, yet far better than a decade ago when extreme pollution was common. Economic growth cannot compensate for an environment people cannot comfortably inhabit. Decarbonization is not merely industrial policy but a quality-of-life imperative.

Over time, these motivations have reinforced one another. What began as response to environmental and energy security pressures evolved into globally competitive industrial strategy. Energy manufacturing scales well, exports easily, and benefits from precisely the system China has spent decades building. The result is a feedback loop: policy support encourages investment, investment drives scale, scale drives cost reduction, cost reduction expands viable applications.

The commitment is now embedded in policy. Business licenses aren’t granted unless green goals can be met. New AI data centers must run on 80% renewable energy.

This raises a question that surfaced repeatedly: Why does cost reduction in renewables, especially solar, remain so intense when prices are already extremely low? Solar is already the cheapest electricity source in many contexts. Further cost cutting seems excessive. The answer: today’s economics are not the endpoint. They are a prerequisite.

At sufficiently low electricity prices, new parts of the energy system become viable. Green hydrogen was the most cited example. Hydrogen won’t replace fossil fuels wholesale, but it becomes economically relevant for hard-to-abate sectors — shipping, certain industrial processes — once renewable energy crosses particular cost thresholds. One company pointed to pilot projects already operating at price points far lower than expected, even accounting for subsidies. Continued pressure on renewable costs isn’t about competing in today’s power markets. It’s about unlocking tomorrow’s.

Through this lens, the willingness to tolerate pressure looks less irrational. Companies aren’t merely fighting over today’s margins. They’re positioning for a future energy system that looks structurally different. Not every bet will pay off, but the behavior we observed is consistent with a system oriented toward long-term transformation, not short-term optimization.

China’s obsession with net zero is real. It is not for show.

Closing Observations: On Cities, Energy, and the Limits of Anecdote

Because people always ask, it’s worth briefly addressing what we noticed outside the factories. After spending most of the trip in city outskirts or in county-level cities like Liyang, the contrast with China’s urban centers was hard to miss, though I’m careful about what conclusions to draw.

In material terms, for example, Liyang’s level of development far exceeds what a “fourth-tier city” would have implied even a decade ago. Infrastructure is modern. Malls are indistinguishable from mid-range malls in tier-one cities. The city feels prosperous and functional, especially for a place that operates primarily as a working city rather than a consumption hub. This convergence is not surprising — the Chinese government has been explicit for years about investing in lower-tier cities and rural areas to reduce visible disparities in quality of life. Still, seeing it so clearly in a place most people would never think to visit was striking. The energy of Liyang is unmistakably different from that of a first-tier city: quieter, more subdued, oriented around work rather than leisure.

The view from my Marriott hotel in Liyang.

Shanghai, by contrast, felt more muted than I remember, though still busy by most global standards. Having visited China regularly for years, I could sense a difference in overall intensity. Some of that may be seasonal. Some likely reflects softer domestic demand and a more cautious consumer mood. Others on the trip remarked that China more broadly felt very atomized, perhaps shaped by e-commerce and screen-centric lifestyles. It wasn’t obvious to me as a frequent visitor and Silicon Valley native, but that’s precisely why context matters so much.

I’m hesitant to elevate these impressions into a broader diagnosis. Street-level observation is a poor substitute for data, and anecdote is highly sensitive to where you go and who you spend time with. A younger friend who recently moved away from Shanghai remarked to me, for example, that she felt the energy was fine — I just wasn’t where the youth were hanging out. Both can be true.

I treat these observations as context rather than signal, the kinds of things people ask about. But they matter far less than the structural forces shaping China’s manufacturing system, its energy transition, and its long-term competitiveness. If this trip reinforced anything, it’s that the most consequential dynamics are often the least visible. They unfold far from the places people instinctively look, in cities like Liyang, inside systems designed less for spectacle than for sustained execution.

For those interested in seeing these systems firsthand, we have several open enrollment trips planned for the coming months. We also work with private groups looking to design custom itineraries around specific sectors or questions. Details are available here.

Liyang is not a City; it is a Node in the R.I.C.E. Protocol.

Rui, this is an exceptional field report. You have successfully peeled back the "Invisible Layer" of System B. What you witnessed in Liyang confirms the core thesis of the ChinArb Framework:

1. The "Designed System" = The R.I.C.E. You noted that Liyang isn't just a cluster of factories but a "deliberately engineered environment." In our model, we call this R.I.C.E. Liyang is a perfect instance of a System B Fractal:

Infrastructure: The dedicated ports and "1220" permit speed.

Chain: Relocating the entire supply chain (not just CATL) to minimize physical latency. This isn't just "Manufacturing"; it is "Industrial Permaculture." They are terraforming the environment so that only high-efficiency organisms (factories) can survive.

2. Profit vs. Endurance (Evolutionary Biology) Your observation that "Profitability is treated as a constraint, not a metric to be maximized" is the key to understanding the West's confusion. System A (Wall Street) plays a Financial Game: Maximize ROE. System B (Liyang) plays a Biological Game: Maximize Survival. In an evolutionary system, "Fat" (Excess Profit) is a liability. "Muscle" (Scale/Efficiency) is an asset. The "Involution" (内卷) you describe is actually Natural Selection on steroids. It creates a species of companies (like CATL/BYD) that are metabolically superior to anything grown in the protected gardens of the West.

3. The Energy Transition as a Civilizational OS You asked why they cut costs even when solar is already cheap. Answer: Because they are not building a "Product"; they are building a Civilizational Operating System. Cheap energy (Solar/Hydrogen) is the base layer code. If the base layer is free, the application layer (Industrial Goods) becomes unstoppable. System B is trying to lower the Thermodynamic Cost of Civilization.

Brilliant work. Liyang is the future, and you are one of the few showing it to the world.

The Underlying Operating System of Chinese Manufacturing: The R.I.C.E. System

https://chinarbitrageur.substack.com/p/the-underlying-operating-system-of?r=71ctq6

I liked your China angle. Looking at real manufacturing advantage instead of just narratives is rare and useful. Curious how you think about risk and structural edge when you form that view. Over at After the Close i talk a lot about process and how external forces shape setups without overwhelming discipline. If you ever feel like swapping notes on that, I’d enjoy hearing your perspective.